The gentle humility of A Change is Gonna Come, Sam Cooke’s 1964 plea for emancipation, belies the simmering fury that inspired it, a fury that reached boiling point in America where this song became an anthem for millions of disenfranchised black people who took to the streets to make that change a reality. It has since been recorded by more than 500 different artists. But Cooke never lived to experience the freedoms his music inspired - he was shot dead in mysterious circumstances 11 days before it was even released.

"Change opens with a regal assemblage of strings, buffeted and borne heavenward by kettledrum and French horn," wrote David Cantwell in The New Yorker in 2015, "all of which build theatrically and then clear out quickly for Cooke's entrance — you can imagine the singer moving downstage into a spotlight, or a camera zooming to close-up. But while the musical setting is grandiloquent, Cooke's tale is down-to-earth. He was born alongside a river that, like him, has never stopped rolling. He's been run off when trying to see a movie downtown and beaten to his knees when asking for help. He's had his moments of fear and doubt, but through it all — big finish — he's nurtured a faith, now a conviction, that change is on the way. Cue tympani."

By 1964, Sam Cooke was a very successful recording artist who had made the rare achievement of crossing over from the gospel music scene, breaking through with his first ever solo single, the self-penned You Send Me, which topped the US singles charts in 1957. He followed it up immediately with a string of Top 40 hits in quick succession, including I'll Come Running Back to You and Everybody Loves to Cha Cha Cha. As the titles suggest, these songs were frothy pop hits - a far cry from the politically charged A Change is Gonna Come.

But by the early 1960s, Cooke had become friends with black icons Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali) and Malcolm X and was growing considerably more conscious of his responsibility to use his fame to communicate something deeper. He was a big fan of Bob Dylan's 1963 hit Blowin' in the Wind and longed to emulate its simple yet profound rhetoric on the concept man's inhumanity to man.

"Cooke insisted that any meaningful concept of integration required an equal amount of white movement toward the black world," writes Craig Werner in his book A Change Is Gonna Come: Music, Race & The Soul Of America. "In 1959, Cooke forced promoters in Norfolk, Virginia, to open black seating areas to whites attending his performance."

The incident that inspired A Change is Gonna Come came in 1963 when Cooke and his band were denied rooms at a Holiday Inn in Shreveport, Louisiana, on the grounds that they were black. Cooke was so angered that he made a scene, which ended with his arrest by the local police. Biographer Peter Guralnick, author of Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke, says Cooke "just went off".

"When he refused to leave, he became obstreperous to the point where his wife, Barbara, said, 'Sam, we'd better get out of here. They're going to kill you.'," according to Guralnick. "And he says, 'They're not gonna kill me; I'm Sam Cooke.' To which his wife said, 'No, to them you're just another ...' you know."

Sometime in the next few weeks, Cooke wrote A Change is Gonna Come. It was recorded in January 1964. In December that year, he checked into a motel in Los Angeles with a woman called Elisa Boyer. Shortly afterwards, he was shot dead by the motel manager, Bertha Franklin, who said that she was forced to defend herself after Cooke has burst into her residence at the motel, wearing nothing but a jacket and shoes, and attacked her. Boyer, who was later alleged to be a prostitute, told police that Cooke had taken her there against her will and that she had escaped, grabbing her clothes - and most of Cooke's clothes - as she fled.

Conspiracy theories abound about the true nature of Cooke's death, with supporters claiming he was silenced by music industry moguls with mob connections who saw Cooke's growing political activism as a threat. No longer satisfied by being a pop star, Cooke had a higher purpose in mind.

"Sam was always into reading," says Bobby Womack, quoted in Craig Werner's book. "He read black history a lot, he read Aristotle, he read The New Yorker and Playboy magazine, I mean he read all the time. Everywhere he went he would look and see where he could get a book – he didn't care what it was about, he would get something."

"That’s the only way you can grow," said Cooke. "Otherwise you're going to write love songs for the rest of your life. "But everything ain't about love."

Learn more about Sam Cooke here:

About the curator: Jon Ewing

After graduating from the University of Keele in England with a degree in Politics and American Studies, Jon worked as editor of a music and entertainment magazine before spending several years as a freelance writer and, with the advent of the internet, a website designer, developer and consultant. He lives in Reading, home to one of the world's most famous and long-running music festivals, which he has attended every year since 1992.

Hello, World!

Latest Posts

Unite and Fight – Mustard Plug

4 March 2021

A high-speed combination of punk chorus and ska verse, Mustard Plug’s singalong Unite and Fight is just one of a sensational 28 tracks on the Ska Against Racism album compiled by Bad Time Records in 2020 to raise funds for non-profit organisations working to improve education, opportunity and justice for black people in the USA and beyond. With a barrelling momentum and a repudiation of violent action, this uplifting song is a call to arms for those of us committed to disarmament.

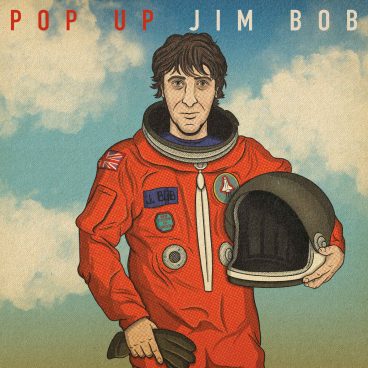

KIDSTRIKE!- Jim Bob

8 September 2020

Celebrating the determination of “one hundred thousand teenagers” to take over the streets of London to save their future from calamity, KIDSTRIKE! by novelist and singer songwriter JB Morrison – aka Jim Bob – is taken from the UK Top 40 album Pop Up Jim Bob released in August 2020 and inspired by the real life activism of countless young activists. But the song is run through with a rueful recognition of the singer’s own fading urge to save the world.

Living for the City – Stevie Wonder

28 July 2020

Inspired in part by the fatal shooting in New York of a ten-year-old black boy by a white plain-clothes policeman, the audacious centrepiece of Stevie Wonder’s experimental 1973 album was a seven-and-a-half-minute meditation on the brutality of black America: Living for the City…

A high-speed combination of punk chorus and ska verse, Mustard Plug's singalong Unite and Fight is just one of a sensational 28 tracks on the Ska Against Racism album compiled by Bad Time Records in 2020 to raise funds for non-profit organisations working to improve education, opportunity and justice for black people in the USA and beyond. With a barrelling momentum and a repudiation of violent action, this uplifting song is a call to arms for those of us committed to disarmament.